As federal lawmakers consider a budget bill that would limit states’ rights to impose restrictions on artificial intelligence, let’s consider a few environmental issues related to this forward march into tomorrow’s AI.

We like to describe data as “in the cloud,” as if it’s invisibly circling our planet. In reality, AI requires a growing number of physical data centers to store and manipulate information.

Energy use globally and nationally is increasing—thanks in large part to the spread of AI. Cryptocurrency mining also takes a toll. Operating data centers to run AI costs water along with energy.

We also sacrifice trees in the process of meeting the energy suck of AI and other data-processing. Other issues abound, too, but let’s focus on these so there’s room for a brief consideration of what we as individuals can consider doing.

Expanding energy cost

Preparing one 100-word email on OpenAI’s ChatGPT takes as much energy as it takes to power an LED lightbulb for 14 hours.

If only one in 10 of every working American uses ChatGPT to write one email a week for a year, those emails use enough energy to power all the households in Washington, D.C., for 20 days.

That’s what The Washington Post reported in a September 18 analysis enlisting the help of researchers at the University of California, Riverside.

The International Energy Agency, meanwhile, estimates that an internet search assisted by ChatGPT uses 10 times the amount of electricity as an unassisted Google search.

ChatGPT users doubled between February and April, to about 800 million users globally.

And that’s just OpenAI. Other corporations including Meta, Apple and Google have their own growing needs for new data centers, and energy and water to run them, to support AI.

For instance, Google’s emission of carbon dioxide from burning coal, oil and gas jumped by 48 percent from 2019 to 2023, thanks mainly to data center energy needs.

At this point, energy demand to support AI is only expected to rise.

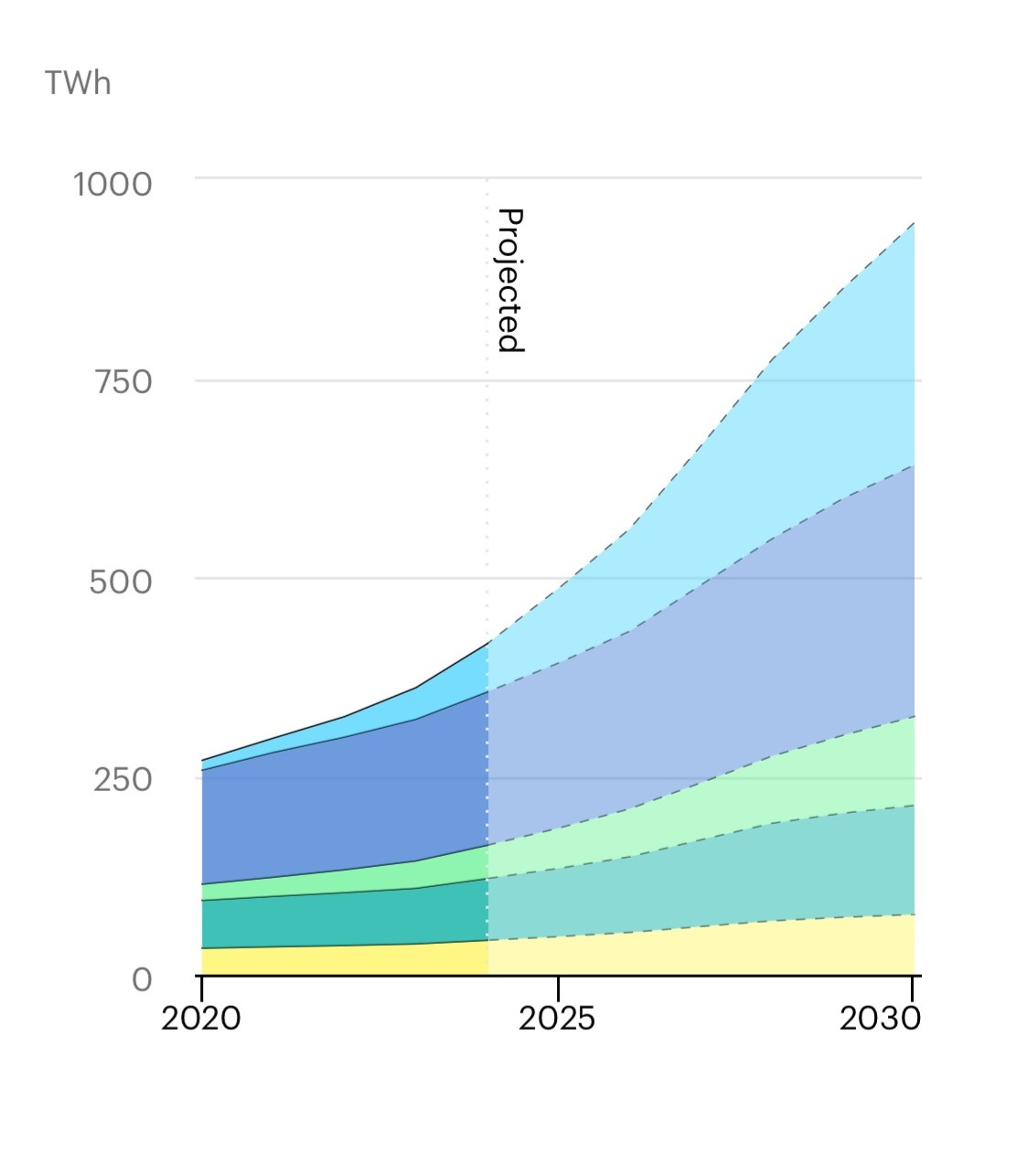

IEA 2025; Global data center electricity consumption, by equipment, in terawatt-hours. Used according to terms of License: CC by 4.0. From the top, equipment includes accelerated servers, conventional servers, other IT equipment, cooling and other infrastructure.

In its first report on global AI, the International Energy Agency last month estimated that global data centers used 415 Terawatt-hours of electricity in 2024. The agency projects that amount will more than double over the next five years.

All of those data centers generate heat. This warms the local environment even as using more carbon-based energy—such as coal, oil and gas—warms the global environment.

Water costs

To cool the equipment powering AI, most data centers tap into local water sources.

Each individual AI-assisted email message of about 100 words costs about a pint-sized bottle of water, according to the Washington Post analysis mentioned above.

Google’s environmental report for 2023, released in July, showed the corporation that year used up about 6.4 billion of gallons of water. Google discharged another 2.3 billion gallons of water, not counting seawater, after circulating it through its system.

The report admitted about 15 percent of Google’s water use, about 1.3 billion gallons, came from areas with high scarcity, such as the U.S. West.

Meanwhile, the corporation just announced on Tuesday plans to expand the AI options on its website. Post technology columnist Geoffrey A. Fowler yesterday provided more details about the plan and what a user can expect from different features.

Spoiler alert: Like existing options, Google’s new AI Mode can still, as Fowler puts it, “confidently provide bad information.”

So on top of the cost of generating an answer with AI, the careful user will also need to spend time and energy, personal and electrical, checking accuracy.

Cost in trees

All of these data centers also take up space on the ground, often displacing nature.

The world now has 8 million data centers globally, according to the United Nations Environment Programme. That’s 16 times the number of centers present in 2012. Each of those 7.5 million new centers erected in the past dozen years likely required some land clearing.

A proposed Alabama project serves as a case in point. The proposed facility, dubbed Project Marvel, would house a 4.5-million-square-foot data processing center on land currently occupied by closed-canopy forest in Bessemer, outside of Birmington.

The project calls for the permanent destruction of 100 acres of forest, as well as massive changes on the adjoining 600 acres, as described in a story by Lee Hedgepeth and Lanier Isom this month for Inside Climate.

At full capacity, Project Marvel would require every year the amount of energy used by the entire city of Birmingham for a whole decade. Residents are concerned the center would suck dry their local stream, the Black Warrior River.

They also worry about the constant noise, the light pollution that will impact their night skies, and potential contamination of lakes with tainted runoff.

And the loss of wildlife habitat is a major concern if the unnamed company is allowed to build the proposed data center. The forest currently supports turkeys, deer, coyotes, racoons and even bald eagles.

What can we do?

In the short term, perhaps the best thing we can do as individuals is limit our personal use of AI. Do you really need ChatGPT to answer a question? Remember, a non-assisted search uses about a tenth of the energy as a ChatGPT query.

That said, I’ve noticed that when I use the default server on my iPhone—Google—it gives me an AI response even though I didn’t and wouldn’t request it.

On my computer, I’ve switched over to Duck, Duck, Go for my search engine. Not only does it leave out the AI (unless you request it), but it also enhances internet privacy. Now I need to get better at remembering to use it on my phone.

Also, consider making an effort to support humans who are doing the jobs that could be done by AI. Many of you on Substack are already doing that by supporting original content here—and we writers certainly appreciate it.

Finding other ways to support people—much like eschewing the grocery store’s automatic checkout to help give a worker a reason for continued employment—can help save energy, water, trees and even jobs.

Other options come up if you know of a data center planned near you. Like the people of Bessemer, Alabama, people around other proposed data centers could watch them carefully.

For instance, they could insist that energy needs be met with renewable energy sources. It still takes mined materials and land to generate, but at least the direct emissions from solar and wind, for instance, don’t include heat-trapping gases.

People who learn of a proposed data center near them can push, too, to require protection of other conservation-worthy land to help account for destruction of forests and other ecosystems on sites used for data centers.

Finally, now is a good time to keep pressure on members of Congress, especially senators, to reject a budget bill that restricts states’ intervention on AI in their jurisdictions.

As the dystopian world portrayed in “The Matrix” becomes more feasible by the day, we humans need to stick together.

After all, we’re the ones with the non-artificial intelligence.

If you have other ideas on how to reduce individual use of AI, please consider sharing it or them in comments below or on the Note feature.