Empathy is a virtue, not a sin

Indigenous view of 'all my relations' suits liberals, progressives

One of my favorite childhood memories involves frolicking in the midwestern grass with six puppies during the late spring of my seventh year. True joy. The puppies actually outnumbered me and my four sisters.

Then, a few weeks into summer, my parents “gave away” the puppies—and Chrissy, their mother—to the so-called humane society. My aunt filled me in on their likely fate, in the days before kill-free shelters. An unbearably sad day became tragic.

Decades later, I would come to recognize how my own empathy for wildlife and nature aligns much better with the Indigenous cultures of the world and the “all my relations” concept they celebrate.

I suspect this is true of many liberals and progressives. Most of us would prefer a society based on win-win partnerships rather than winner takes all domination.

Here, I argue we would do well to follow the lead of the Indigenous peoples and cultures who recognize the deep importance of empathy for those beyond one’s own skin—and now is the time.

‘The sin of empathy’

Increasingly, empathy for animals, or even humans, doesn’t fit well into our domination-focused white culture. Now many of its leaders and thinkers are even bad-mouthing empathy itself.

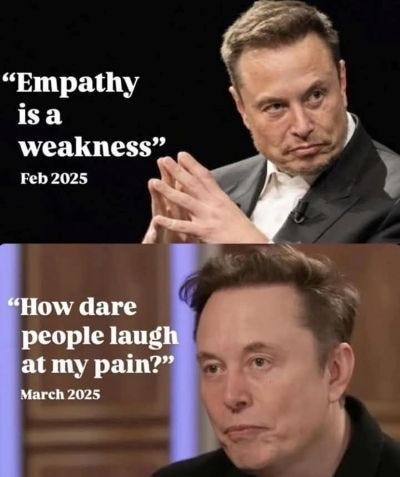

For instance, in a February interview on the “Joe Rogan Experience,” Elon Musk declared “the fundamental weakness of Western civilization is empathy.” In The Dispatch, Alastair Roberts noted this dig seems designed to goad liberals and progressives.

On another front, as Michael C. Rea reported in a March 12 opinion piece for Religion News Service:

Joe Rigney’s new book, The Sin of Empathy, released late last month, tells us that empathy “often leads to cowardice” and “frequently leads to brazen malice and cruelty.” Rigney is a Fellow of Theology at New St. Andrews College and an associate pastor under Doug Wilson at Christ Church in Moscow, Idaho. (Both Wilson and Christ Church have been in the news for, among other things, their advocacy of Christian nationalism.)

The Christian nationalists conveniently ignore that history shows us Jesus Christ, whose teachings founded modern Christianity, often demonstrated empathy.

Meanwhile, Donald Trump has long rejected empathic behavior in favor of its polar opposite: cruelty.

“The cruelty is the point,” as his niece, Mary Trump, explained in her 2020 book, Too Much and Not Enough: How My Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man.

He also rewards cruelty in others. Consider his appointment of former South Dakota Governor Kristi Noem as Secretary of Homeland Security.

In a 2024 memoir, Kristi Noem described how she shot her 14-month-old wire-haired pointer puppy named Cricket. On a pheasant hunt, Cricket was “going out of her mind with excitement and having the time of her life.” Then, Noem took her to a farm where Cricket was “the picture of pure joy” as she chased chickens. So, as Noem wrote, “At that moment, I realized I had to put her down.”

(If you’ve ever wondered if some conservatives prefer to see suffering over joy, there’s your proof. And here’s Stephen Colbert’s take on that incident if you want some humor to temper the outrage.)

The title of Noem’s memoir, No Going Back, takes on new meaning in the context of her cruelty toward immigrants, as demonstrated with her callous photo opp in front of shirtless Venezuelan men behind bars in an El Salvadoran prison known as the Hellhole.

In a Substack post yesterday, Mary Trump highlighted the likely innocence of some of the men now imprisoned in the Terrorism Confinement Center. Those shipped off included Kilmar Abrego Garcia, an El Salvadoran man deported in error.

Today, a federal judge ordered his return to his home in Maryland. We’ll see if the Trump administration complies, despite its earlier insistence the deportation can’t be reversed.

That’s the kind of cold-hearted approach that follows lack of empathy.

Empathy as a moral value

Empathy seems to be a trait that links many of us together on the Left—we’re concerned about those outside of our sphere.

Men understand the need for women’s rights, white and Indigenous people recognize Black Lives Matter, and citizens from birth stand up when immigrants are treated unfairly and even with cruelty. Liberals and progressives can empathize with abused people of all colors and ethnicities, as well as animals and nature.

But we potentially have much to learn from the Indigenous peoples who treat wildlife, land and water with respect.

The Lakota phrase Mitakuye Oyasin often translates as “all my relations.” This reflects a worldview of feeling interconnected to not only their human relatives and other humans, but also to non-human and other-than-human beings. The latter include bears, salmon, redwoods, even mountains and rivers. Even fire.

Gregory Cajete, an Indigenous scholar with the Santa Clara Pueblo, noted the people of his culture have a long-standing relationship with animals, plants and the land.

“As we sustain the land, the land also sustains us in the context of this notion that we are related—not only to the plants and to the animals, but we are actually very much the land itself,” Cajete said during an Earth Day TEDx talk in 2015.

Now a professor emeritus with the University of New Mexico, Cajete was still serving as its director of Native American Studies at the time of the talk.

“The Spirit of Sustainability is coming alive again,” he said. “We call this ‘Indigenous mind rising.’ One can also say it is the time when we must, as people of this Earth, begin to once again respect and honor—and in a sense begin to follow—the music and the song and the dance of Kokopelli. He beckons us on.”

The fertility of the land, and agriculture, are honored in the ancient deity Kokopelli among the Pueblo and other southwestern tribal nations.

Time of the Seventh Generation

This time in North American history is seen as particularly important to many Indigenous Americans, as the young people born roughly between 1980 and 2000 are viewed as the long-awaited Seventh Generation.

Ann Marie Chischilly, as director of the Institute for Tribal Environmental Professionals, referenced this during the closing plenary of a 2020 biannual National Tribal and Indigenous Climate Change conference.

Chischilly reminded everyone that the visionary Black Elk, whose words were immortalized in Black Elk Speaks, famously said in the 1800s that those born seven generations from his time would restore the hoop of life.

“That generation, I’m happy to say, is here with us today. I’m raising one,” Chischilly said. She noted her son Shonto, an Oglala Lakota or Sioux, has a direct ancestral connection to the Lakota medicine man Black Elk.

Coming back to this theme in the 2022 conference, she said, “They will get us through, and they will get the rest of the world through. They’re rising up throughout the entire world.”

Allying with Indigenous peoples

A traditional medicine wheel. Courtesy of Empowering the Spirit

The Anishinaabeg, which include the Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi nations, similarly recognize the current time as one calling for the people supporting sustainability of life to band together.

Robin Wall Kimmerer, a Citizen Potawatomi Nation member and ecology professor, talked about this in her 2013 book, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants:

The Seventh Fire prophecy presents a second vision for the time that is upon us. It tells that all the people of the earth will see that the path ahead is divided. They must make a choice in their paths to the future. One of the roads is soft and green with new grass. You could walk barefoot there. The other path is scorched black, hard; the cinders would cut your feet. If the people choose the grassy path, then life will be sustained. But if they choose the cinder path, the damage they have wrought upon the earth will turn against them and bring suffering and death to earth’s people. …

So much has been forgotten, but it is not lost as long as the land endures, and we cultivate people who have the humility and ability to listen and learn. And the people are not alone. All along the path, the nonhuman people help. What knowledge the people have forgotten is remembered by the land. The others want to live, too. …

The path is lined with all the world’s people, in all colors of the medicine wheel—red, white, black, yellow—who understand the choice ahead, who share a vision of respect and reciprocity, of fellowship with the more-than-human world. Men with fire, women with water, to reestablish balance, to renew the world. Friends and allies all, they are falling in step, forming a great long line headed for the barefoot path.

It’s all too easy to imagine us on the path to a blackened landscape—especially as the Republican administration seems determined to create chaos by firing and reorganizing wildland firefighters while promoting timber harvesting policies many are convinced would make wildfires even worse.

But there’s still a chance to head that off and even turn it around.

So let’s get behind the Indigenous leaders who know how to live on the Earth without turning it into a cinder-covered landscape.

Then, together, let’s choose the grassy path that sustains life.

I bet it has puppies.

Melanie Lenart writes Eco-Logic posts three times a week, typically focusing on Indigenous topics on Fridays.

My two terriers take a nap as I write this post. Photo by Melanie Lenart

I would love to hear other people's thoughts about the weird way the Republican administration derides empathy, or thoughts on the idea of following Indigenous ways to the soft green path. Or anything else this post brings to mind for you.