Among tribal nations, Mother Earth always has a seat at the table. At a 2024 forum, this chair was set up to in the planet’s honor. Photo by Melanie Lenart

When I wrote a book about how our living planet responds to climate change, I had hoped to describe some Indigenous practices as possible “land management prescriptions.”

But the Indigenous people whose perspectives I sought wanted to talk about land stewardship, not management. They didn’t want to apply a one-size-fits-all prescription to land policy.

And they persistently shifted the focus to Mother Earth.

At the time, I considered their responses a bit vague. Years later, though, I better understand the cultural clash that occurred when my management-oriented questions collided with their Indigenous worldview.

The Indigenous worldview, as described by Leroy Little Bear in an earlier post, involves perceiving the world as waves of energy rather than particles of matter. It also involves seeing humans as part of nature rather than outside of it.

These differences contribute to how we treat nature.

Now, as a white woman who regularly writes about Indigenous issues, I would like to share here some thoughts on why I consider the Indigenous worldview more suitable for a sustainable existence on the planet that supports us all.

‘It’s the economy, stupid’

The dominant culture, the white culture of Capitalism, focuses on what it says matters: the bottom line. Tangible goods. Purchasing power. Profit.

While working on my doctorate in Natural Resources and the Environment at the University of Arizona, I found extolling the virtues of a natural area didn’t go far unless you could invoke a monetary value.

So, for instance, surveying visitors to an area about how much they would theoretically pay for those fabulous views would compete with how much money the site theoretically could produce via logging or mining. Even then, the tangible timber or copper often would win out in our society.

For example, mining and logging fall under appropriate “uses” of public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management, but conservation didn’t count until last August. As a result, leaving water in a stream wasn’t considered a good “use” of it, but taking it out for irrigation or mining somehow was.

We were just starting to get away from that approach to using our public lands during the previous administration.

Biden’s Interior Department in August enacted the Conservation and Landscape Health Rule (also known as the Public Lands Rule). Basically, it allows the BLM to consider conservation alongside other land use options.

Roughly 92 percent of 200,000 public comments supported the shift to allow conservation to stand alongside mining, recreation and cattle grazing.

But now the Trump administration is working quietly to remove conservation as an option for BLM land. The Office of Budget and Management posted a notice earlier this week to rescind the popular rule that was helping the BLM balance its management of the 247 million acres of public lands it manages.

This is where the dominant culture has brought us. The ruling Republican administration doesn’t even want us to have an option of conserving public lands for any use besides human industry or entertainment.

Land and water stewards

My own frustration of dealing with a system that can’t see beyond a land’s economic value to humans found some relief when I began working more closely with people from tribal nations.

As a postdoctoral researcher, I crossed paths at conferences with Indigenous land stewards. But my education in Indigenous thinking really took off when I worked for five years in a faculty position with Tohono O’odham Community College.

I admire how the Tohono O’odham, whose ancestral land hosts my Tucson home and crosses well into Mexico, maintained their culture and even their language through hundreds of years of upheaval.

I’m not saying I found everything in their culture preferable to my own. It’s not my culture. But I especially appreciate how the O’odham culture, like that of every other Indigenous culture I’ve come across, holds a deep respect for the land and water.

In just one example, the Tohono O’odham Nation used some of its allocated Colorado River water to bring a river back to life in their San Xavier District. Groundwater withdrawals in nearby Tucson had dried it up.

The O’odham could sell the allocated water, if they put profit above nature. Instead, they use it to support an organic farm and to restore a non-public riparian area near the San Xavier del Bac Mission in Tucson.

When I went to the river with students on a field trip, it was a beautiful lush site, with cottonwoods and willows that had grown about 60 feet tall in the two decades since the restoration project began.

David Tenario (left) of the San Xavier District explains how the Tohono O’odham are using Colorado River water to restore the river site. Photo by Melanie Lenart.

Their sister tribe, the Akimel O’odham, did something similar with their stretch of the Gila River. They also placed solar panels above the canals bringing in their water allocations, a win-win move that prevents water loss from local evaporation even as the renewable energy produced helps limit future temperature rise from burning coal, oil or gas.

Those are just a couple of examples. I’ve talked about others previously in Eco-Logic:

Many tribal nations practice land stewardship by working with fire instead of trying to banish it from the landscape (a ploy that has backfired).

More than a hundred tribal nations joined the effort to protect the drinking water at the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. From there, “Water is Life”—a phrase previously expressed on many tribal nations—reverberated out into mainstream culture.

Tribal colleges have been shifting toward solar power, with several in North Dakota providing examples.

So many good examples arise from cultures that put nature over profit.

Cultural distinctions

Many other cultures practiced Earth-sustaining methods such as these—including many European cultures before they were overrun by their own invading colonizers, such as the Romans or Vikings or the long arm of Great Britain.

Even in our money-focused culture, many non-Indigenous individuals buck the trend by working on projects to protect nature.

In particular, those working for environmental non-governmental organizations do admirable work, often partnering with tribal nations to carry out nature-based projects.

But most would agree it’s a struggle to protect nature amid the dominant culture, where material wealth is worshipped.

On the flip side, many North American Indigenous peoples have dealt with efforts to convert them into the dominant mindset, such as by forced enrollment in boarding schools or campaigns to push them off their lands and into the city.

Yet, based on my interactions, the underpinnings of their cultures still, somehow, were handed down generation after generation, along with some of the traditional seeds and traditional knowledge.

As well as knowledge gleaned over the generations, though, it’s a way of thinking, one that makes nature a partner.

It’s a cultural willingness to fit oneself into the landscape rather than dominate it that proves crucial.

Selso Villegas invites participants in the Soutwest Adaptation Forum to bang a drum as they consider their relationship with Mother Earth. Photo by Melanie Lenart

‘Human effort to change the world’

The late Phillip Miguel, a beloved colleague at Tohono O’odham Community College who taught the history course I took, told us “Indigenous” really means “of the land.” By his definition, it could apply to any culture that works mindfully with their natural surroundings, especially generation after generation.

I think about that sometimes as I seek to steward the land where I live, with its expansive view of the distant mountains and the leafing-out mesquite trees. I can even see Baboquivari peak, a sacred mountain to the Tohono O’odham.

About a year ago, I attended the Southwest Adaptation Forum in Tucson organized by five groups, including the University of Arizona Indigenous Resilience Center. It attracted many of my former university colleagues alongside several I knew from the Tohono O’odham Nation.

For the initial interactions in small circles, someone had even set up a chair for Mother Earth (featured in the photo at top).

Before re-arranging chairs into a more conventional setting with tables, conference participants took turns banging on a drum held by Selso Villegas, a Tohono O’odham elder who encouraged everyone to share thoughts from their heart on how they remember their relation with Mother Earth.

“We need to start not talking in rhetoric like ‘Indigenous versus non-Indigenous,’ ” Villegas said. “We have to say ‘human effort to change the world’.”

I appreciate his invitation to include all of us who are working for the planet and its people. At the same time, I think we would do well to follow the lead of Indigenous peoples if we truly want to find a sustainable way to exist on this North American landscape.

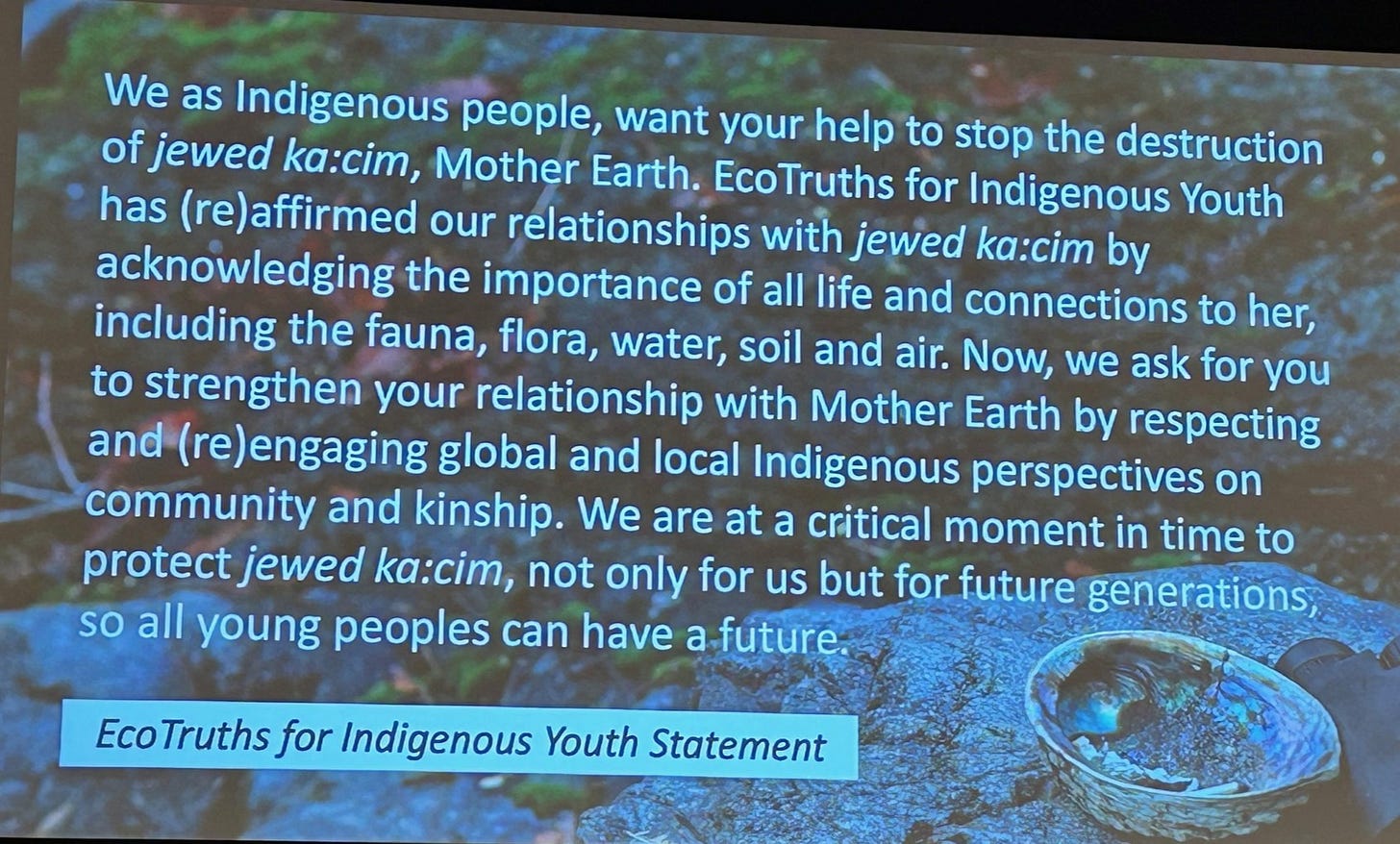

Judging from a slide shown at the forum, the young people from the tribal nations would sure appreciate it.

Thank you for such a thought provoking piece. I love the idea that any people who steward their land and water respectfully across generations are potentially indigenous. It opens up the possibilities that with guidance more of us can return to our indigenous roots, belonging to each other and the land. I'm in the UK, all too aware of what damage my forebears have done, so wondering, in the context of all that is happening what our next practical steps are.