Old-growth forests face chopping block

‘Emergency’ logging plans attempt to roll back forest protection

Remnants of logging in Siuslaw National Forest Photo by David Herasimtschuk

Despite their ability to cool the climate, both locally and globally, big trees and old growth stands in our shared public forests face renewed attacks from all fronts of the Republican administration.

On Thursday, those in charge of our public forests responded to the president’s executive order by pledging to open about 112 million acres of our national forests up for logging. The response suggests agency officials don’t feel a need to wait to see if the Senate passes the U.S. House of Representatives January bill to expand timber harvesting.

We can count on legal challenges from the non-profit environmental groups working to protect our public forests.

But right now, one of our best hopes for protecting them may come from the chaos and confusion generated by other Trump directives and corporate concerns about fluctuating policy and breakable contracts.

Forest Service issues directive

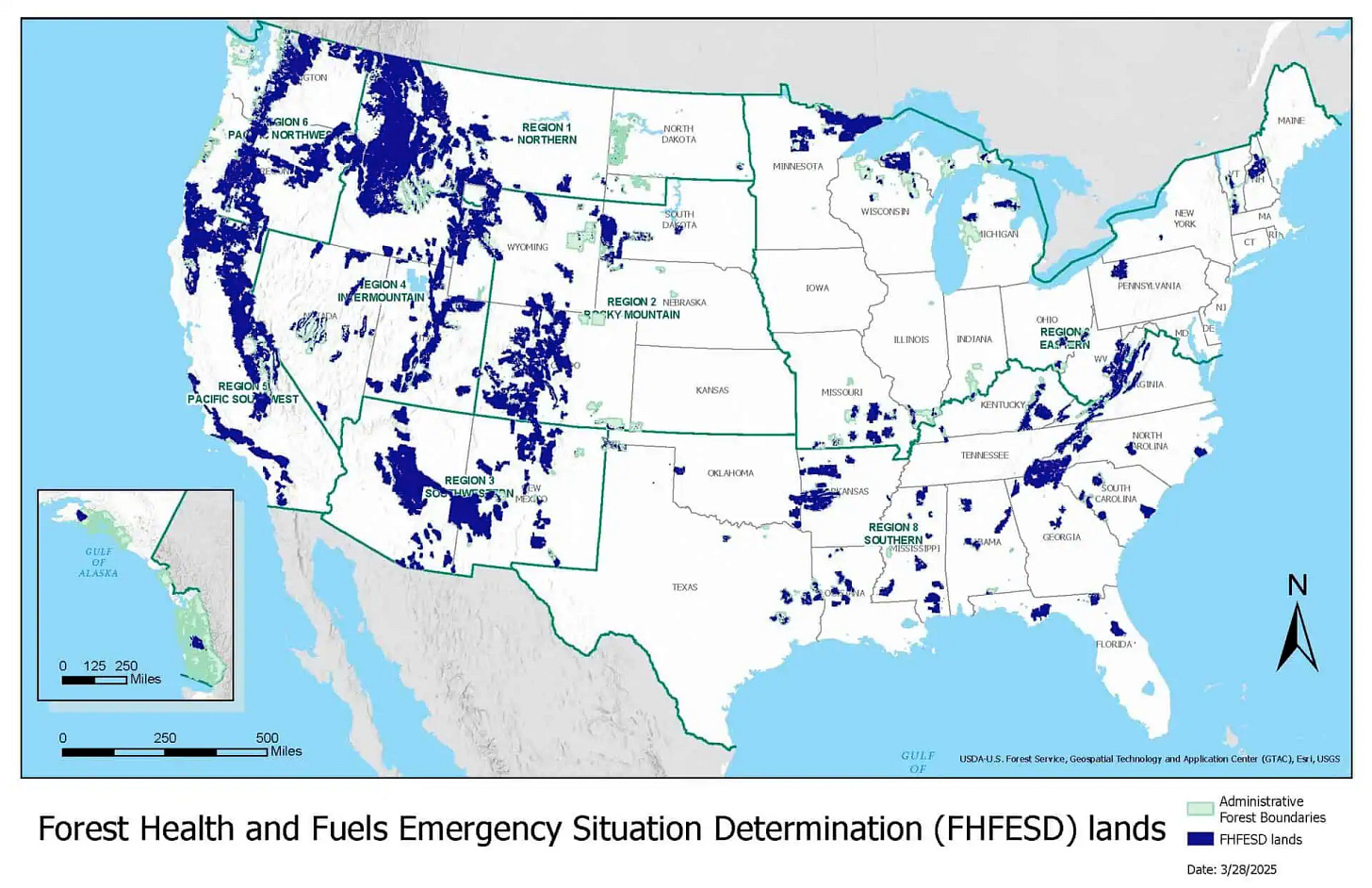

The secretary of the U.S. Forest Service’s parent organization, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, declared an “emergency situation determination” in a memo last week, citing a need to log more of our national forests. It claimed wildfire hazard alongside the need to promote the domestic timber industry.

The forest service’s acting associate chief, Christopher B. French, promptly directed underlings “to release direction for using Emergency NEPA, Endangered Species Act, and other regulatory authorities to streamline and simplify our permitting processes” within two weeks of his April 3 memo. NEPA is the National Environmental Protection Act, which requires consideration of environmental impacts before taking action.

In other words, as instructed, they’re seeking to blow past laws of the land that require considering whether proposed actions will harm the environment and wildlife. The attempted roll backs include areas protected for cultural reasons through the National Historic Preservation Act.

The plan appears to be to give away the trees in our national forests for a song. Here’s how the memo describes it: “Finally, all agency timber sales will use base rates or minimum rates, where appropriate, based on the Emergency Authorizations outlined by the Secretary.”

Western forests in particular face challenges as indicated by a map highlighting blue targeted areas.

Recent challenges to Oregon’s national forests highlight what’s at stake and just why these old-growth western forests are so valuable for other reasons besides timber.

PNW efforts to protect large trees

When we think of Pacific Northwest forests, we probably think about the mammoth spruce, fir, hemlock or even sequoia trees that dominate the temperate rainforests of the West coast. The generally drier forests east of the Cascade Mountains run more toward Ponderosa pine, but they tend to loom larger than similar forests in the interior West.

In part, that’s because of Oregon’s 21-inch rule. In 1994, the forest service restricted the logging of big trees—those 21 inches wide or more—from the shared public forests we call our national forests.

A Trump effort to eliminate that rule right before he left office in 2021 was denied last year by a judge who ordered the agency to reinstate the restriction while it assesses more thoroughly the potential impacts of the proposed change.

However, several Oregon-based scientists and conservationists are concerned the restriction against logging the bigger trees in national forests will face assault from the “emergency” legislation to open more of our public forests to logging.

As Steve Pedery of the conservation group Oregon Wild shared with me in an April 8 email:

The Trump admin is directing USFS staff to identify obstacles to more commercial logging, so I'd expect a whole range of administrative protections for mature and old-growth forests, roadless areas, threatened and endangered fish and wildlife, etc., will eventually be on the chopping block.

It is also telling that they are framing their logging goals in terms of there being an "emergency" situation and logging volume being a national security issue. That seems to set the stage for them to ultimately try and suspend Congressionally-legislated environmental protections and/or ignore judicial rulings.

Oregon evaded earlier Trump attack on big trees

Others concerned include David Mildrexler, an ecologist with Eastern Oregon Legacy Lands who led research published in 2020 to estimate how many trees in six national forests in the Pacific Northwest would be affected if the Forest Service lifted the so-called 21-inch rule.

David Mildrexler demonstrates the size of a 21-inch wide tree and how it’s measured. Photo courtesy of David Mildrexler

Mildrexler and his colleagues used Forest Inventory and Analysis measurements collected by forest service employees from more than 3,000 plots east of the cascades in Oregon, Idaho and Washington. They included every tree from five key species: Englemann spruce, grand fir, Doulas-fir, western larch and Ponderosa pine.

They used this data to assess how many trees from the five target species fell into the 21-inch diameter size class—i.e., those with trunks getting close to two feet wide.

The researchers found that about 3 percent of the trees in these forests qualified for protection under the 21-inch rule. Yet this small proportion of large trees represented about 42 percent of the carbon stored above ground in these forest stands.

“And the thing that really blew my mind about that was that the people that were proposing to change the rule didn’t know the answer to those questions,” Mildrexler said during an early April Zoom interview. “And those are fundamental questions, right?”

He and his team pulled in equations designed for these specific species to estimate how much the visible portion of each measured tree weighed—a value known as “above-ground biomass” in this context.

By dry weight, a tree is roughly half carbon. And all that carbon originated as airborne carbon dioxide, the main heat-trapping gas behind the ongoing warming of the planet.

Converting carbon dioxide into solid forms of carbon keeps it from heating the air. That’s how these big trees help cool the global climate.

“It’s crucial, if we want to get carbon out of the atmosphere and keep it in the forest, to protect these large trees,” Mildrexler said during a 2022 presentation. “We simply do not have time to cut down 100-year-old trees. In the next two decades, we will not recover any of those services. So, this is a crucial moment.”

Photo by David Herasimtschuk

Forests protect against overheating

Forests keep their local environment cooler, too.

Their extensive canopies stay far cooler than unforested surfaces, to the tune of 20 to 40 degrees Fahrenheit. Their shade protects soil water from excessive evaporation. Shade and evaporative cooling, meanwhile, keep the climate below the canopy cooler too.

That all changes once the trees have been clear-cut, logged, harvested or even, in some cases, “thinned”—which can be destructive events themselves, despite the mild-sounding word.

Former forestland lacking trees, especially large trees, have lost the regulatory control they once had over the water cycle. Rains can initiate serious floods. Dry times can cause soils to quickly desiccate.

What’s ahead

Unfortunately, the Republican administration isn’t willing to acknowledge climate change. So all the cooling power in the world—and the world’s forests draw down about one-third of humanity’s emissions of carbon dioxide from burning forests and fossil fuels—likely won’t add up to any influence on this decision unless it’s via the courts rather than the administration.

The congressional acts mentioned in the federal agencies’ memos have long been used by environmental groups in legal challenges of agency decisions regarding public lands.

We can be sure some of them will sue to challenge the legality of the forest service’s plan to short-circuit these acts as well as the National Historic Preservation Act under the pretense of a national emergency.

But the challenges may well face a U.S. Supreme Court rife with Trump appointees.

And, as we’ve seen from other situations, such as the accidental deportation of Kilmar Abrego Garcia, the Supreme Court sometimes lets the administration get away with flouting court decrees.

A less visible but potentially viable slow-down of the logging plans could result from the clashing of several Trump policies.

Basically, the expected economic downturn from Trump’s tariffs might lead to a sluggish market for home construction, as Elizabeth Weise explained in USA Today, noting much of the timber imported by the United States supports the construction industry.

The construction industry also may find it challenging to gear up thanks to the Republican administration’s attacks on immigrants, as a New York Times article notes.

With the IRS planning to help identify immigrants working without a permit and even legal immigrants such as Kilmar Abrego Garcia subject to random deportation to an El Salvadoran prison dubbed “The Hellhole,” it’s almost certain that many immigrants are high-tailing it out of our country or deciding against trying to come here on a temporary visa.

The latest saga in the attack on immigrants involved more than 300 students here legally suddenly having their student visas revoked, with orders to leave the country within a week.

It’s a devastating blow to our universities, our international reputation and, of course, the individuals who weren’t even allowed to stay while they finished off the expensive semesters they started.

But it’s also a sign to the business community that legal contracts mean nothing to this administration.

The on-again, off-again nature of Trump’s policies might make timber barons and home builders hesitant to carry out the necessary investments to take advantage of the boon they are being offered. After all, they’re not going to ramp up supply if there’s no demand for their lumber.

I also can’t help but hope that Tesla’s recent economic dive—largely attributed to boycotts due to CEO Elon Musk’s attacks on federal workers, private data and federal norms—might make timber companies think twice about pursuing practices destined to put them at risk of national boycotts.

It’s a sliver of hope for some of our most iconic wilderness areas and old-growth forests, but it’s quite possible a chaotic economy could limit the Republican administration’s efforts to destroy the beauty and cooling power of many of our treasured national forests.

If so, maybe the Trump administration is right about the enemy being within: The most immediate actions that might keep timber companies at bay are coming from inside the house. The White House.

Thanks Melanie. All very depressing.

Thanks, Melanie, for keeping us updated.

Btw… went to the USDA memo you linked to. Disgustingly nauseating how they state in a bald-faced lie how opening up old growth forests will “…improve fish and wildlife habitat.”

Great work. Keep it up!