What can the world do about horrific tropical forest loss?

Solutions include supporting local landholders, Indigenous communities

The hottest year on record really did a number on the world’s forests last year, although forest policy—or lack of it—also played a defining role in the destruction.

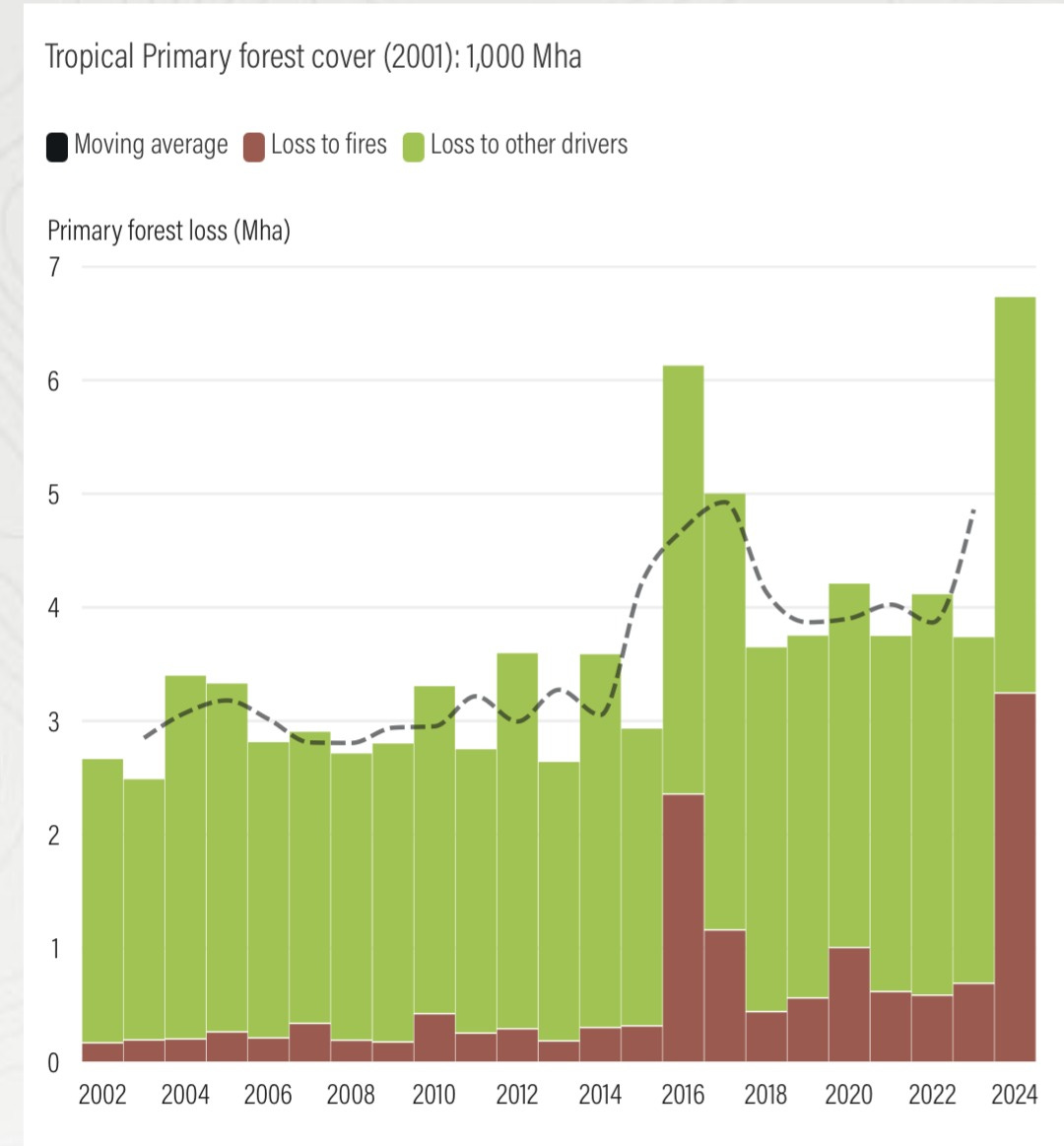

In the United States, logging continued to take down about three times as much tree cover as wildfires in 2024. But fire played a big role in boreal forests of Canada and Russia and drove almost half of last year’s 16.6-million-acre decline of tree cover in tropical primary forests.

That’s a take-away from information released last week and a Wednesday webinar hosted by the World Resource Institute to interpret results. A scientific paper on the assessment is expected soon in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Brazil—which is set to host this November’s annual international talks on climate change, COP-30—accounted for about 42 percent of last year’s tropical tree cover loss.

“Fires are not part of the natural cycle, like in the boreal forests,” Mariana Oliveira, the institute’s director of Brazil’s Forests and Land Use Program, told webinar participants. “Combined with these high temperatures fueled by climate change, we saw these huge fires used in agriculture spread over the primary forest.”

Researchers from the institute, the University of Maryland’s Global Analysis and Discovery Lab and Google used high-resolution data from satellites paired with the artificial intelligence of Google Deep Mind to generate this disturbing report on global tree cover loss.

Tropical forest tree cover loss in 2024 registered an 80 percent jump compared to 2023. Numbers given in million of hectares (Mha). Each hectare contains 2.47 acres. Image courtesy of the World Resource Institute’s Global Forest Watch.

What’s behind the loss?

High temperatures from climate change and drought plagued tropical forests, especially in areas already fragmented or degraded by logging, crops or cattle.

The “wildfire” category doesn’t distinguish between naturally occurring wildfires and fires set intentionally by humans. Information from regional experts in the tropics suggests agricultural fires set in 2024 carried further than may have been intended.

Climate change made droughts hotter and can shift weather patterns. The weather pattern known as El Niño also loaded the dice for less rainfall in some regions, including Latin America.

On top of that, past deforestation poked holes in formerly intact forests, drying them out and making them more susceptible to burning.

In contrast, large swaths of intact forests maintain forest moisture. They protect the surface from evaporation and even help generate rainfall.

Forest loss also releases heat-trapping gases such as carbon dioxide and methane, exacerbating global warming. In contrast, intact forests pull these gases out of the air—most notably carbon dioxide, but also methane.

Even with the ongoing deforestation, the world’s forests typically absorb about a third of the carbon dioxide released by humanity’s burning of forests, coal, oil and gas.

Nearly comparable rates of tropical forest cover loss in 2016—with about 15 million acres damaged—didn’t deter forests in the long term from carrying out this important service. But too many years like 2016 and 2024 will challenge forests’ ability to rein in global warming.

Along with drought and record-breaking temperatures in 2024, governmental policy played a big role in countries that saw some of the highest rates of tropical forest cover decline.

Regional hot spots

Several institute specialists reported on dynamics in hot spots, such as Bolivia, Colombia, Brazil and the Congo. Indonesia represented a bright spot in the 2024 data, with slightly reduced forest loss compared to the previous year.

Brazil saw about 7 million acres of its forest cover burned or razed to some degree. Oliveira pinned some blame on a large-scale drought that affected three-fifths of the country—the worst drought Brazil has seen in seven decades.

Similarly, high temperatures and drought in neighboring Bolivia helped spur the 2024 loss of tree cover across 3.7 million acres—an astonishing 4 percent loss in the country’s 10-percent share of the Amazon rainforest.

Stasiek Czaplicki Cabezas, a Bolivian researcher and data journalist, said Bolivia’s political system is deliberately structured to increase deforestation with its “booming, often illegal, land market.”

He said the systemic deforestation is marginalizing Indigenous populations as soy, sugar cane and, lately, African palm crop up where rainforest once stood.

In Colombia, forests suffered, too, as “armed actors” used deforestation as a peace talk bargaining chip, explained the institute’s senior adviser on Colombia, Joaquin Carrizosa.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo showed the third-highest rate of forest cover loss in 2024, after Brazil and Bolivia. Degradation of forests for charcoal production was a major cause of tree mortality, along with agriculture, explained Phanuella Djanteng, an associate with the institute’s Congo Basin Engagement program.

Results above are shown in millions of hectares. There are 2.47 acres in every hectare. Image courtesy of the World Resource Institute’s Global Forest Watch.

What can countries do?

Indonesia saw a slight decrease in tropical tree cover loss in 2024 compared to the previous year.

Tomi Haryadi, director of the institute’s Food, Land and Water initiative in Indonesia, said the region’s success story relates to sustainable partnership initiatives between locals and international companies and governmental action to suppress illegal deforestation.

For Indonesia and beyond, Haryadi suggested increasing the productivity of existing farmland in the tropics could help break the cycle of intentionally burning down primary forests to tap into fertile soils.

Technical and financial support for small landholders could help stabilize the situation, Brazil’s Oliveira agreed. Funding mechanisms are a hot topic at international climate change meetings.

In the Congo, Djanteng said outside funding to transition into renewable energy could help reduce the widespread practice of cooking with charcoal—made by charring wood.

Helping Indigenous peoples and locals gain land tenure, potentially through international agreements, also would help protect forests, she said. Others heartily agreed.

Globally, evidence indicates the Indigenous peoples of the world tend to preserve forests and maintain high rates of biodiversity within them.

Beef demand spurs market

Connecting the dots between illegal deforestation and global markets would be another way to help reduce tropical forest cover loss, Carrizosa suggested. Cattle ranching, he said, relates to beef demand in China and Middle Eastern countries.

“We hope that illegal beef—coming from illegal areas, for instance, in the Amazon— can be visibly traceable,” he said. That could potentially curb its export.

Several speakers supported collaboration among countries, including by incorporating the Forest Watch tool that allows for detection of tropical forest fires in real time. The interactive website gives users a chance to review the data, including for 2024.

“These numbers should just push us to work harder, not to just lose our dream of having these areas protected and managed by their own people,” Carrizosa said. “In the end, our water, all around the world, and food, all around the world, will depend on the proper working of this system.”

See this Global Forest Watch post for more details on the regional drivers of forest cover loss in 2024. Next week, I plan to touch on the 2024 losses in the context of climate variability and global warming, with a brief foray into how forest cover in modern times relates to that of warmer climates of the distant past.