Amazon trees gorging on extra carbon dioxide

The widening girth of Amazon trees reflects access to more carbs.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: It’s been a long year. I find myself wanting to focus on the positive during the holiday season—as a gift to both readers and myself. So, through at least Three Kings Day on January 6, I plan to focus on the organic, or Gaian, side of the equation in the saga I sometimes think of as Mother Earth v. the Machines.

Our living planet has been taking climate change in stride for eons. This fall, scientists provided evidence showing tropical forests are still doing so even as our modern climate heats up.

Hundreds of researchers worked together recently to re-measure 188 plots of intact Amazon forests across the Amazon. In a September paper in Nature Plants led by Adriane Esquivel-Muelbert, they concluded intact old-growth Amazonian forests are growing bigger.

The study showed that intact rainforests can handle the heat, as long as it comes with an abundance of their favorite food, carbon dioxide.

Trees bulk up with carbs

The cooperative international effort showed intact forests, even ancient ones, are continuing to collect carbon dioxide from the air. A heat-trapping gas, carbon dioxide has been spurring on warmer temperatures throughout the Earth’s long history.

But carbon dioxide is also plant food. The researchers surmise the extra carbon dioxide in the air from burning coal, oil and gas is fattening up trees in these ancient groves.

Trees capture these floating molecules and pluck off the carbon atoms, then add water to transform them into carbohydrates. Among other things, the studied Amazonian trees used the resulting carbs to bulk up their leaves, their branches and their noticeably larger trunks.

Please note the authors’ focus on intact, or what they label “undisturbed,” forests across the Amazon.

Other researchers have found that forests are often less resilient in places where there’s logging, human-set wildfires to replace trees with crops or cattle, road building and urban expansion. Some stands may even release more carbon than they retain as respiration and decay convert stored carbohydrates back into carbon dioxide.

In some ways, this research was a regional upgrade of the global 2024 Nature study led by US Forest Service research scientist Yude Pan that I wrote about earlier this year. Pan and her colleagues also concluded carbon dioxide was spurring on forest growth across the globe, in both recently planted forests and intact old-growth.

But let’s keep our focus on undisturbed forests, as Esquivel-Muelbert and her colleagues did.

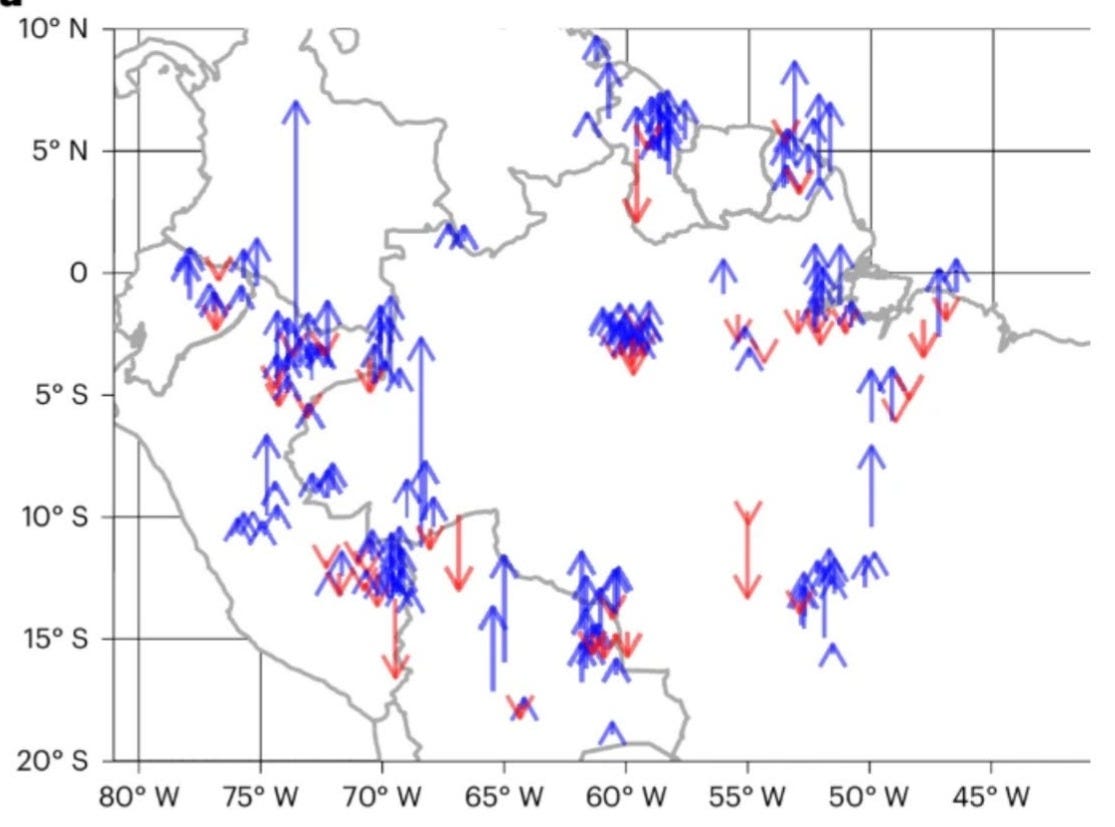

Researchers re-measured trees in intact Amazonian forests in Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, Guyana, French Guiana, Bolivia and near the borders of Venezuela. Blue lines indicate trunk basal area increases by stand, while red ones show declines. Image cropped from paper and used according to Open Access license.

Trees share the wealth

Overall, the amount of area in the Amazonian plots covered by tree trunks increased by 3.3 percent a decade over the three decades of the study.

And Esquivel-Muelbert and her colleagues found it wasn’t a matter of some trees thriving while others shriveled.

The biggest trees, those more than about 16 inches in diameter, widened so much that the researchers found support for one of the patterns they were testing—Winner Takes All.

Under this scenario, the trees with the most mass would continue to accrue more mass at the expense of the other trees. The big trees would, in effect, hog the resources.

But they found the smaller Amazonian trees, the ones starting out below about 8 inches in diameter, also flourished. This lent support to an alternative scenario they called Carbon-Limited Benefit, where the shaded trees grow fastest over time.

Shaded understory trees sometimes have trouble getting enough carbon dioxide under the forest cover. After all, a closed canopy blocks winds and thus airflow.

Having the extra plant food—carbon dioxide—in the air, though, apparently allowed shaded trees to thrive even if their larger brethren were sucking up a lot of carbon dioxide themselves.

Medium-sized trees also showed growth increases, though less dramatic gains than the biggest and smallest trees.

In short, Amazonian trees thrived together. I would describe the results as a Share the Wealth situation.

The one class of trees that didn’t do as well were the tiniest. Fewer seedlings or saplings established under the umbrellas of these closed-canopy stands than expected. But presumably the fall of a large tree or other canopy-opening disturbance would allow seedlings to get a foothold.

In the meantime, the general lack of smaller stems arguably could impart additional fire resistance to these stands.

Tropical rainforests typically only burn at the hands of humans. Still, the lack of smaller stems in these old-growth stands might make it more difficult for people to start fires there, as the stands include fewer small stems susceptible to drying out enough to serve as tinder.

A planetary feast

The research from the Amazon upholds the premise by some of us researchers that plants generally expand and flourish in warmer climates, and shrink in area and size in colder climates. This conclusion is based on a variety of evidence from geological time frames going back hundreds of millions of years.

I even argue that trees have evolved to thrive in warm climates when carbon dioxide levels run relatively high.

The first woody plants emerged from wetlands about 300 million years ago. They started out tiny, but over time evolved to include massive redwoods and flowering hardwoods, including the big trees that loom in the tropics.

During their ongoing evolution, the climate has fluctuated dramatically. Shifts include glacial periods when ice covered Chicago and much longer hothouse periods, when permanent ice didn’t even cover the poles.

In other words, the organic system underlying and supporting our living earth has hundreds of millions of years of experience in handling climate fluctuations.

Now if only we humans would respect their role and leave them in place to do it. The understanding that plants, including trees, are adapting to the warming climate might help us resist doing into something crazy, such as spewing pollution to “dim” the sun.

True, we are in a moment where the plant and animal species holding up our life-support system are under attack from all sides: for construction of AI data centers; from mining; from weakening US environmental laws, including those designed to protect endangered species and public forests; from wildfires; and, of course, from logging.

At some point, though, the pendulum must swing back to protecting our living planet, much as we saw when Earth Day was launched in 1970.

In the meantime, we can take heart in knowing intact tropical rainforests can maintain planet-supporting conditions, when left in peace.

Next week, I’ll branch out to talk about how even a barren landscape can lead to impressive regrowth following the removal of stresses that prevent trees from growing back, highlighting the remarkably quick recovery of some mesquite forests in southern Arizona.