Gaia versus AI

Resource demands of this technology could destabilize our living planet

Many among us seem to think the Earth is merely a stomping ground for wheeling and dealing rather than a living system that supports us all.

This includes, of course, our current president.

Donald Trump sees a rose garden and covers it with concrete. He eyes public lands, even sacred lands, and envisions oil fields, logging operations and copper mines.

He side-eyes clean air and water, pushing us back into the Age of Pollution. He promotes the deregulation of resource-demanding cybercurrency and Artificial Intelligence.

Gaia can’t work under these conditions.

At least not well.

Our living planet—dubbed “Gaia” in the scientific theory launched by the late James Lovelock and Lynn Margolis—needs nature in all of its manifestations to help regulate chemical cycles and stabilize temperature and humidity.

The race to develop AI, given existing circumstances, could strain our water, power and land in ways that might make it difficult to bounce back. For instance, AI-serving data centers proposed for Tucson and Phoenix, if built, could usurp as much electricity as all the citizens and businesses currently in those metro areas.

If we don’t slow down on our efforts to pave the way for AI, we risk driving off a cliff we didn’t even see ahead.

We know what to do

I always hated it when yet another scientist or group of them laid a timeline on a doomsday prediction. Usually, it’s 10 years. Then, when the decade ends and large-scale disaster still has not manifested, others start to wonder if scientists are being melodramatic.

But then, I always thought we’d turn this Earthship around by now.

We’ve known what to do to protect our planet since 1970, when the United States celebrated its first Earth Day:

Stop using fossil fuels—namely, coal, oil and gas—to generate electricity and run vehicles.

Clean up the air and water.

Protect forests, wetlands and other natural systems from destruction.

In the early 1970s, we passed laws to clean up our air and water. In the half a century since, we’ve taken great strides in developing affordable solar and wind power, and even electric vehicles, all of which could help replace fossil fuels.

We also have gained a far more thorough and nuanced understanding how trees serve as carbon filters, cleaning the air throughout their long lives, and how forests themselves help cool climate and even generate local rainfall.

Morning dew settles onto trees in Siuslaw National Forest. According to the biotic pump theory, forests draw moisture-laden air to them. Photo by David Herasimtschuk. Used with permission.

The passage of former President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act in 2022, with its support for solar and wind power and tree-planting efforts, started heading us in the right direction.

And his administration signed more than 180 stewardship agreements with tribal nations giving Indigenous peoples a key role in stewarding our public lands.

It seemed we might actually make that hairpin turn toward a more sustainable society.

The wrong turn

Then we put Trump in the driver’s seat.

Trump and his sycophants have been working to claw back $27 billion allocated to communities and individuals for solar energy. He launched efforts to offer up our shared public lands for fossil fuel projects, private ventures and extensive logging.

Instead of honoring Indigenous peoples as knowledgeable stewards of the land and waters, he threatened to remove citizenship from Native Americans. Fortunately, that ploy failed.

So here we are, approaching 2030, and the chances of us reining in climate change seems slimmer than ever.

In Tucson, we’ve just emerged from a week of temperatures ranging around 110 degrees. Other Americans could tell similar stories, based on “real feel” temperatures that account for humidity—some of them while under a pall of wildfire smoke.

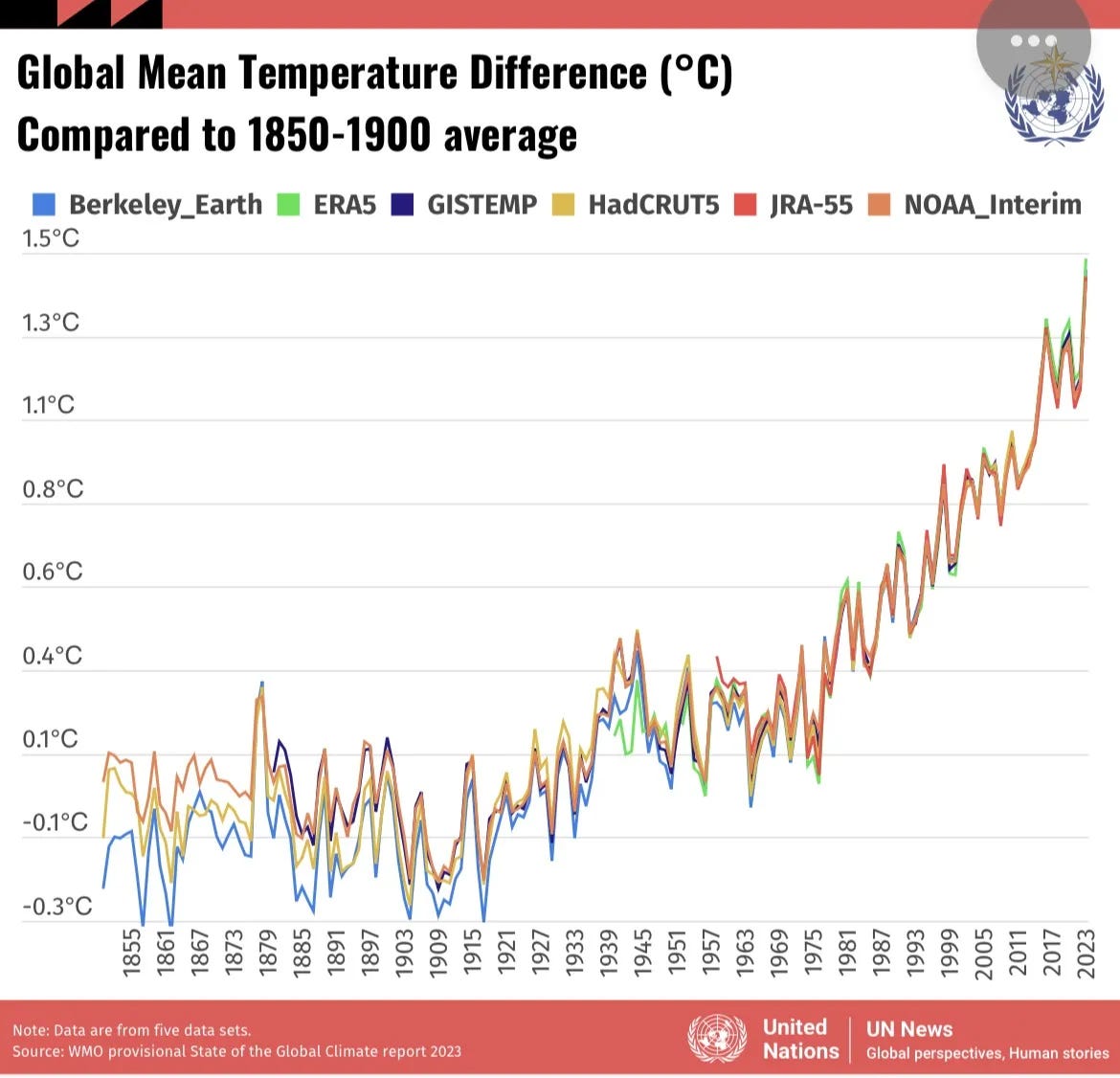

The last decade contains the 10 hottest years in records of global temperatures since 1850.

The World Meteorological Organization compared several different analyses to conclude global temperature in 2024 was 1.55 degrees Celsius higher than the long-term average. That’s 2.79 degrees Fahrenheit.

What can Gaia do?

The Earth is remarkably resilient. Gaia has shown again and again that she can bounce back from natural disasters and even some human-made ones.

Watching Puerto Rican rainforests rebound from a major hurricane in 1989, for instance, gave me new respect for the “fragile rainforests” I had come to study. These were vibrant jungles.

Seeing images of forests and wildlife thrive in the decades after the Chernobyl nuclear power plant meltdown similarly feels reassuring.

But there are limits to what Gaia can do in the face of simultaneous attacks on crucial systems that moderate temperature—our forests, grasslands and wetlands—while we continue to add heat-trapping gases.

As I wrote in my University of Arizona Press book, Life in the Hothouse: How a Living Planet Survives Climate Change:

Wetlands have been called the planet’s kidneys, given their role of purifying a dilute toxic stew of chemicals into potable water.

This function only works in a healthy system, though. The ongoing destruction of wetlands leaves our planet with the equivalent of one kidney to handle the toxic load of a meth addict who subsists on French fries and whiskey.

Forests have been called the planet’s lungs. Again, our hacking away at these systems equates to asking an asthmatic chain smoker to run a marathon.

Are we asking Gaia to do too much with too little?

Old-growth forests remain crucial

I would argue, and have done, that protecting remaining forests and wetlands is at least as important as reducing society’s emissions of heat-trapping gases such as carbon dioxide.

Before humans entered the scene a few million years ago, forests were far more able to roll with the climate changes.

Evidence from deep time reveals forests and wetlands expanded during warm times of the past—even during hothouse climates, when polar ice caps melted away. Left to their own devices, forests expanded into polar regions yet also remained elsewhere, including in the tropics.

Old-growth forests, reduced to remnants now, are worth fighting for. We need them for climate regulation and to adapt to the extra heat. Young forests help, too.

Meanwhile, the advent of AI threatens to serve up compounding problems to our forests and other natural systems.

First, AI requires land and water both in its own data centers and in the construction of electricity plants to serve its voracious appetite.

That’s on top of the land, water and power lost to mining the metals, silicon and rare earths needed for the operation of data centers serving AI. Gavin Mounsey’s excellent post yesterday viscerally illustrated how mining destroys ecosystems down to bare rock.

Also, there’s no way we can energize data centers with renewable sources such as solar power while simultaneously shifting our nation’s electricity plants away from fossil fuels—especially given Trump’s undermining of solar power.

So, after many years of feeling many scientists’ doomsday hype exaggerated the risk, I can no longer downplay the very real dangers we face if we continue down this road.

Let’s test those brakes

Gaia can only deal with warming climate if we leave enough nature, including old-growth forests, in place. Already our planet seems to be destabilizing.

AI and other Republican policy could tip the balance.

If we continue at the pace urged by Trump and the billionaires pushing for AI development, it could send us over the edge—probably in a self-driving car.

But here’s the thing: That hasn’t happened yet.

Theoretically, there’s still time to maneuver.

Let’s slow down—city by city. And state by state.

The outcry in Tucson that kept a huge Amazon data center from establishing in our drought-ridden city—so far, anyway—is exactly what we need around the country to head off this AI-fueled future disaster.

Fortunately, states did retain the right to regulate AI, despite Trump’s efforts to prevent that. At the state level, we can start by dismantling the tax breaks in at least 36 states that actually encourage the construction of water-guzzling, energy-consuming data centers.

If we don’t act now, we may be looking into our rearview mirror a decade later to regret, in hindsight, that we missed the turn-off.

After all, AI can only crash our planetary system if we humans give it the power to do so.

Only the heart that is connected to an extraordinary mind could write such an exceptional piece. Listen up America!

Incredibly well stated and presented!!! You just fluidly diagrammed the planetary crisis we are standing in right now, from the 70’s to the present while giving us exact steps to reverse it! This one article is a virtual treasure map! I don’t think a person could get such valuable information by studying for a decades and college or reading stacks of books. This article lays everything out. This simple diagram is worth a world podcast tour. This clear explanation needs to be heard!